Banning books stunts personal and spiritual growth

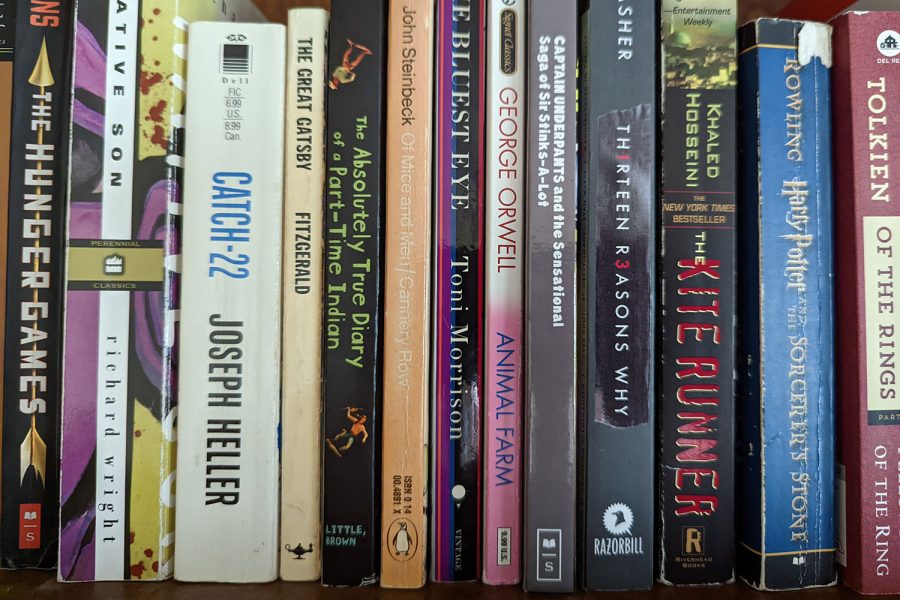

These are some of the books that have been banned or challenged somewhere in the United States in the last 20 years.

Ray Bradbury’s 1953 masterpiece Fahrenheit 451 tells a story of a dystopian society in which firemen, who start fires rather than put them out, burn each book made known to them. Bradbury displays the modern American city as a numbed dystopia, lacking the love of nature and meaningful conversations. Nearly 70years later, the tendencies of dystopian societies formerly only conceivable in literature are beginning to seep into our daily lives. Literature seems to be in evident danger.

The first book to be banned on American soil was Thomas Morton’s New English Canaan, published in 1637. The New English Canaan was a culmination of the hatred Morton had for the Puritans and how their settlement ran. The book was taken with so much offense and insecurity that he was later exiled for his piece of writing. Four hundred years later, we still face the same issue; choosing to be offended by purposely challenging literature.

PEN America, a nonprofit organization that aims to defend and celebrate free expression in the United States and worldwide, estimates that in 86 school districts, over 1,145 books have been banned from libraries and classrooms. The topics most prevalent in these books are LGBTQ rights and racism issues. The most widely banned of all books is said to be 1984 by George Orwell, followed by The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, rounding out the top three is Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger. Why ban books that portray dystopian societies in which they no longer exist? Why ban books that open the minds of their readers? Why ban books that make us uncomfortable due to their challenging topics?

To dive deeper, we must explore what is considered to be a strong pro for book banners; parents should have the right to decide when their children are exposed to certain material. The true miracle of life is something I have yet to comprehend at the age of 16. The desire to protect your child from certain materials is perfectly normal. Keeping your son or daughter away from explicit imagery, substances, or situations is a parent being a good parent. But when a child yearns for more, for different scenery, for growth, a parent concedes lovingly and desires to support their child through it all. There is no growth when the scenery never changes. A child will become a teenager, a teenager becomes an adult. Restricting a child’s material beyond their developmental years (birth to the age of five) obstructs their ability to succeed in the “adult world.” In the words of Jeff Mangum; there comes a sad time to “wake up your windows and watch as those sweet babies crawl away.”

I digress. How can we find common ground in this argument? Could we put ratings on books like we do movies? Yes, this would seem to be a logical system. Yet challenging works of literature have been around longer than the idea of an atom, so why start now? Placing a rating system on books would seldom do more than the “explicit” label that looms at the bottom of an album. However, parents still have reason to feel uncomfortable about the books their child is reading, even more so if they feel their child is not yet mature enough to handle the book’s subject, or if handicaps would affect how their child might react to the nature of the book. If parents believe their child cannot handle a specific work of literature, should they not just disallow their child to participate in the reading, rather than disallow a whole school or district to read the book?

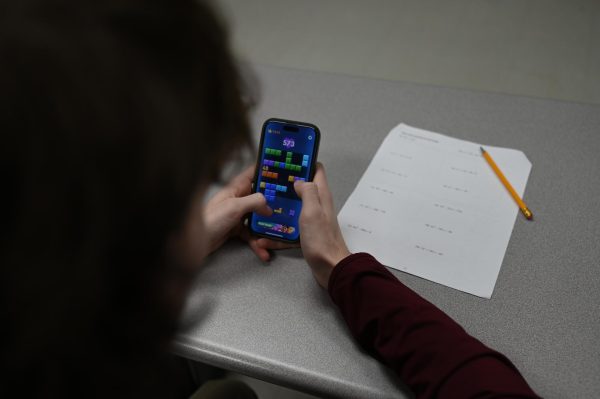

In a time where the world is reading less than ever recorded, there is little to be gained by further reading restrictions. Banning a good book is like banning adventure, personal growth, self-discovery, and exploration. Research shows that to grow spiritually, one must make themselves uncomfortable. If a book makes the reader uncomfortable, its purpose is fulfilled.